This article appeared in the National Times 29 November — 5 December 1981 p 17

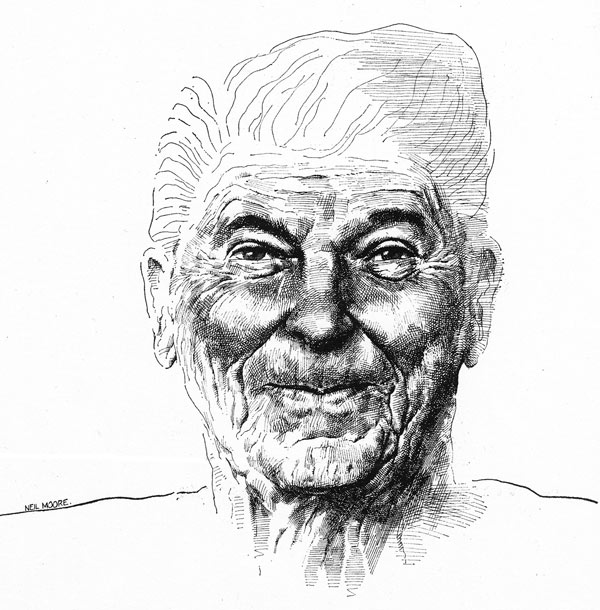

Reagan: peeling away the layers of illusion

In a poll taken before the presidential election last year, Americans were asked to single out the most important quality in a president. Some 51% said it was leadership, 43% said it was honesty, and exactly 3% said the policies a President adopted wherel what mattered most. Ronald Reagan was elected because he has an air of authority. In America, it is the image which prevails, and Reagan cantered through the first nine months in office because he uncannily resembles a president. Last week in the face of several political setbacks Reagan pulled off a typically theatrical manoeuvre. He vetoed a money bill essential to the functioning of government, and, looking uncommonly fierce, told reporters he was determined to halt excessive government spending. "He is firm, resolute and he means business," said Larry Speakes, deputy press secretary for the White House. Reagan Hangs Tough, bragged a front-page banner headline in the New York Post (a newspaper which has conspicuously avoided all front page mention of the President's recent troubles with his senior staff). Reagan scowled in earnest from an accompanying photograph." He means business," said the caption. It was exciting stuff, a reminder that this was the President who promised to balance the books. But Reagins brief battle with Congress was all sound and fury, signifying nothing. The excess he found intolerable was half of 1% of an appropriations bill worth well over $400 billion. Is performance last week was a sham. In 1969, responding to protests about the rule of President Richard Nixon, his Attorney General John Mitchell said: "watch what we do, not what we say." In March, 1981, when the liberals were emitting cries of anguish over the supposed savagery of Reagan's budget, the President was interviewed by editors of the New York Daily News, and his words could come back to haunt him. Speaking (one assumed) of those affected by the budget cuts, he said:..."as soon as they stop running and yelling that the sky is falling, I think they're going to find out that we're not going to upset things that much." |

The president's hard of hearing, and prone to rely on genial generalities when stuck for an answer. But on that occasion his unconscious more or less upstaged him, and he uttered what looks increasingly like the truth. His rhetoric is close to revolutionary. He constantly vows to turn most of the functions of the Federal Government over to the states, saying that those who do not like it "can vote with their feet" (meaning move). He has repeatedly promised to slash the Washington bureaucracy, as if it is so much Virginia creeper, and asserted specifically that he would dismantle the departments of Energy and Education. Both departments remain untouched, and all that the President's men managed to abolish we're several minor agencies, such as the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms. On the campaign trail last year he would boast that when he was Governor of California, "we stopped the bureaucracy cold." The fact is that while Ronald Reagan was Governor, the number of public servants in California increased by 21 per cent. Perhaps because he was an actor, in Reagan's mind the word is often (if sincerely) taken for the deed. As president, he repeatedly promised a balanced budget by 1984. Overtaken by brute fact, he blinked and now accommodates a deficit of say, $100 billion. For all his tough talk, the President appears unwilling or unable to make hard choices. His politics are tailored by public opinion and he is flexible to a fault. Concerned above all about his own popularity, he governs by consensus and is stymied because no-one ever agrees. To really reduce government expenditure, he would have had to re-organise the system of twice-early adjustments to the age pension, which run a little ahead of cost-of-living increases. Reagan had Richard Schweiker, his Secretary for Health and Human Services, propose the essential changes. There was universal outrage, the politicians baulked, and the President left that sacred cow out grazing. |

Defence expenditure was declared untouchable from the start. It actually increased strongly. Reagan had campaigned hard on a promise to weed out "waste, fraud and mismanagement," but when he came to office, the Pentagon was left to manage its business as usual, and the Navy went on placidly refurbishing a battleship (militarily obsolescent 30 years ago) at a cost of about $800 million. In March, James Watt, Secretary for the interior and a character who recurs later in the story, said:"... We will use the budget system to be the excuse to make major policy decisions..." They did tackle the perennial bogies of the Republican right, skimping on subsidised school lunches, food stamps and the like, eliminating federally funded legal aid for the poor, and abolishing the work training program for deprived youth. While all this may have been philosophically gratifying, it was economically insignificant, and hardly amounted to "major policy decisions." Pres Reagan has certain ideas how his world ought to work. Not long after reaching the Oval Office, he replaced the portrait of Jefferson with one of "Silent Cal Coolidge, a president remembered for little but saying "the business of America is business." Jefferson was the dangerous Democrat who wrote the passage in the Declaration of Independence which goes: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal..." Equality is a principal "I don't accept," said one of Reagan's senior aides. On the campaign trail, Reagan habitually resorted to lines which – like his affable aw shucks presence – involved a reassuring essentially small-town America. The problems of government were only a question of common sense pruning. " It isn't a shortage of fuel, it's a surplus of government." America's rightful place in the world was no more than a matter of self-assertion. "Shouldn't we stop worrying whether someone likes us, and decide that once again we are going to be respected in the world." In Reagan's view this world appeared to have scarcely changed since 1947 when he was president of the Screen Actor's Guild and appeared as a friendly witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee hearings on communists in the motion picture business. "I don't know the basis of communism," said Reagan. "From what I hear I don't like it because it isn't on the level." |

In August 1980, at at Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) convention, Reagan said an arms race with Russia was necessary to avoid "surrender" or "defeat", and became the first candidate endorsed by the the VFW since the turn of the century. Soon after assuming office, Reagan said that the Soviet leaders accorded themselves "the right to commit any crime, to lie, to steal..." He probably only meant to say "they aren't on the level" but his rhetoric runs away with him, and, asked to explain the remark a few days later, the fledgling, 70-year-old President said: "They don't subscribe to our sense of morality. They don't believe in an afterlife. They don't believe in God or a religion." Other presidents have sometimes escaped from the difficulties at home (with Congress intractable, the bureaucracy rubbery, the people unpredictable) by concentrating on foreign affairs. Richard Nixon liberalised relations with China. Carter played host to Begin and Sadat, and the Camp David accords were signed. But President Reagan has exhibited startlingly little interest in foreign policy. Early this year, his twitchy Secretary of State, Alexander Haig, marched determinantly into the limelight, and, flourishing a State Department "White Paper", announced that Cuba and Nicaragua was supplying arms to the rebels of El Salvador. To stop the spread of godless communism, he threatened a blockade of Salvador. The President did not seem particularly perturbed, either way, but his aides persuaded him that Haig's campaign was a distraction from the own budgetary battles on Capitol Hill and Haig was told to cool it. The possibility of a blockade resurfaces now and again (most recently last week). The rhetoric is Right and that is about it for the old, Cold War warriors around Reagan. The Senate has voted to lift the bants on the sale of arms to the governments of Argentina and Chile, but the only action on the foreign front was the overblown and marginal victory the President achieved on the sale of AWACS (Advanced Airborne Control Systems) to the Saudis. Some said it was unwise to help stock the arsenal of a private family, some said the AWACS could change the balance of power in the Middle East, but at the core of the debate as the White House saw it, was a domestic question of Presidential authority: Reagan could not be seen to lose. |

|

Indeed he has shown no desire to mediate in the Middle East. The only foreign policy speech he made did not mention the region.

Last week an editorial in the New York Times asserted: "until last week, the Reagan administration's foreign policy was little more than a booming weapons business. Outproducing the Russians was going to make them docile, or broke. Selling the Arabs more arms would win security for Israel. Replacing Soviet arms with ours in central America would pacify revolutions. Selling arms to Pakistan would keep it non-nuclear. Even the nostalgia for a "two Chinas" policy would be served by sending weapons to both. "With the notable exception of Namibia, Reagan looked at the world through gun sights. "Harping on American vulnerabilities, the President left the impression that he was too weak even to define his diplomatic aims or to negotiate with anything but a stick..." These unusually unrestrained remarks culminated in the suggestion that this desolate picture had completely changed on the previous Wednesday. That was the day the President delivered "A simple...Yet historic message", saying that the Americans would not deploy Cruise and Pershing 11 missiles in Europe if the Russians removed the medium-range nuclear missiles they already had in place. It happens that serious disarmament negotiations begin in secret, but this speech relaying a suggestion Soviet President Brezhnev had earlier and explicitly rejected, was beamed to Europe: the Europeans have been extremely jittery about the American alliance since Reagan made his off – the – cuff comments about fighting a "limited" nuclear war on their soil, comments later embroidered by Alexander Haig, who spoke about a "demonstration" nuclear explosion Europe. The President's speech the other week was intended to reassure the Europeans, but 350,000 people in Amsterdam demonstrated against the deployment of nuclear weapons a few days later. There was little sign that Reagan's offer was anything but a propaganda ploy – Pentagon and state department officials said afterwards that "a vital element" in the American approach to arms control negotiations with the Russians (which start November 30) was that their plans to install medium range nuclear missiles in Europe would proceed until there was a breakthrough in the talks. In short, the situation was exactly what it was a month ago. Not that you would have guessed it from the American press. A front-page article in the Washington Post enthused: "President Reagan's first major foreign policy address yesterday was a masterful performance that took the high ground in the quest for nuclear arms control. It was a speech that could wind up changing the tone of his Administration. Well, it was a magnificent performance. President Reagan has the actor's knack of conveying utter faith in what he is saying, at that moment. The substance is almost irrelevant – it is the fervour that comes across. So it seems almost churlish to point out that in one particular, his arms control speech was a complete reversal. |

Last year Reagan like and arms control negotiations to "appeasement", but that was on the campaign trail, and no political candidate expects to be tied to his platform. This year, as President, he said with absolute conviction that there was no "sense in sitting down at a table with the Russians" until they had changed their attitude and their activities in Afghanistan...Poland...Cuba... In May, Reagan told a class graduating from West Point that he mistrusted arms control treaties. "No nation that placed it's faith in parchment or paper, while at the same time it gave up its hardware, ever lasted long enough to write many pages of history." Edwin Meesa III, now the White House counsellor, once said about his boss: "He understands the need for realistic compromise." But Reagan responds to gusts of public emotion or opinion more momentarily than ever compromise demands. It is sometimes said he lacks, well, substance, but that understates it. President Reagan is as insubstantial as the image on a flickering screen. He invokes the past that does not drag it's dead weight behind him. Addressing a campaign crowd in Philadelphia, Mississippi, where three civil rights workers were murdered in the 1960s, Reagan talked about states rights, which is the rallying cry of southern racists, and was later (no doubt genuinely) surprised when accused of being anti--black. The speech Reagan always delivered on the campaign trail (and in one way or another he has campaigned for the presidency since 1968 when he made a grab for the Republican nomination), was naturally nipped and tucked according to the crowd before him. That is what politicians do. But Reagan's presidency is as much a matter of the prevailing winds. Every night his pollster Richard Wirthlin has interviewers telephone 150 people throughout the nation. Their reactions are fed into computers, and by morning Reagan's handlers have the results ready to stitch up to the minute opinions into speeches and policies. No other President, including LBJ, who used to carry the statistics around in his pocket, has polled as extensively and constantly as Ronald Reagan. His popularity has slipped a bit lately and is about the same as Jimmy Carter's was four years ago. A Gallup poll taken at the start of November showed that 53 per cent of the electorate approved of the way Reagan was doing his job. But he is, and always has been, notably less popular with women, who think of him as "reckless" about war. The Republicans are worried about it and a presidential aide recently said that the way to adjust the image was that "Reagan is going to have to develop a compassion issue." As that makes plain, the issue they seize on does not matter much one way or the other – it is the projection which counts. Last year the Los Angeles Times reported that a Reagan-for – President commercial purportedly showing him signing a bill to cut taxes in California was actually a photograph of him signing a bill to liberalise the abortion law. Reagan's camp did not seem especially flustered by the disclosure, and as they hummed and hawed about whether they'd can the commercial, they managed to create some other spectacle for the media. |

It worked, of course. A few days before the election, a trade magazine reported that 443 of the nation's daily newspapers had endorsed Reagan for President (while poor Jimmy Carter, unable to conjure up a mirage by the fourth year of his presidency, had 126 endorsements). All American politicians play mainly to the media but Reagan's aides have proved particularly adept adept at managing his "public" appearances. In the week that Budget Director David Stockman was reprimanded for lifting the curtain on the budget compromises, and security adviser Richard V. allen reminded of a $1000 sweetener in a White House safe, the magazine US News and World Report obliged Reagan's need for some counter-publicity with a gossipy article about his "private" life. A full page was devoted to the First Family's consumption of a vodka and orange juice at the cocktail hour. Mrs Nancy Reagan told the world that her husband does not raid the icebox before retiring. "But she often eats bananas in bed, she reports, rather than crunchy apples, which would keep him awake." The photograph on the facing page "released by the White House" had the couple in identical red sweaters and white shirts. In case anyone missed the point, the President's trousers (and socks) were royal blue. Mrs Reagan had her shoes kicked off, and in sight, which is about as deshabille as she's ever been in "public". Both of them were in armchairs, with trays of food in front of them, and the caption said "like many other Americans, the Reagans sometimes eat off trays in front of the TV". If you think this is taking over much notice of a simple photograph, you have misunderstood the ferocious attention this Presidency pays to the details of its image. And understanding of the style of power is not without its uses. Reagan has handled Congress more effectively than Carter ever could. One reason is that he and his advisors understand how to exploit the Mystique of the Presidency. During the budget debate earlier in the year, and again when it looked as if the Senate might be reluctant to sell AWACS to the Saudis, Reagan's aides identified the wavering votes and the President himself was brought out to lean on them. This ploy has worked so well that Reagan has been more successful in handling Congress than any president since Franklin Roosevelt. But Rooseveldt was an intelligent pragmatist – if an idea did not work, he cheerfully scrapped it. Reagan re-moulds his opinions from day to day, but he has clung tenaciously to a particular theory – supply-side economics – and a particular promise, tax cuts, as if he has mastered few other ideas. The deepening recession helps suggest how the economic theory works in practice. The revelations of the budget director David Stockman, recently published in Atlantic Magazine, indicated that the Administration already knew in May that the economic program was a failure, and still Reagan clings to it, as if the prestige of his presidency depends upon it. |

Although he is superb at delivering a prepared speech, Reagan has been most unimpressive at his few press conferences. He turns questions about foreign policy over to advisors, or fudges. He relies on his own affability. He gets things wrong. After one such performance the other week, David Broder of the Washington Post, perhaps the leading political reporter in the country, observed that Reagan had given the impression of someone under a great strain."The comments on Capitol Hill and in the embassies suggest that the tension and anxiety the President displays when answering questions about his own policies are beginning to cause concern among those here and abroad who look to the President for leadership." He went on to suggest that Reagan has such a shaky grasp of the policies for which he is formally responsible "that he has the dickens of a time remembering what he is supposed to say about such and such a subject." It probably does not matter much if the President is a deep thinker or not. But Reagan does not do his homework, either. Carter and Nixon would spend several days swotting up before a press conference. The manager at the helm of the nine-to-five presidency gives it and afternoon, before he takes his famous nap. His greatest personal charm is his relaxed style, and it may yet prove to be his abiding political weakness. Reagan can act his part (as long as he does not have to think on his feet) but seems peculiarly incapable of adapting it to the resistant realities. In recent weeks there have been recurrent problems with his staff. The one public scandal concerns security adviser Richard V. Allen, who accepted $1000 from a Japanese journalist, then forgot all about it. Allan (who was no great shakes as a security adviser, either) is likely to be asked for his resignation, within a week or two, and as quickly forgotten. But the nine-to-five President has made other dubious appointments, and has a habit of appointing foxes to mind the chicken coops. James Watt, his Secretary of the Interior, has managed to antagonise both conservationists and mild-mannered traditionalists by opening up wilderness areas for mining. James Miller III, Reagan's new chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, a body which exists to regulate business, announced at his first press conference that "free enterprise is becoming less free in the name of something called consumerism." Miller immediately proposed that the commission stop enforcing a truth-in-advertising rule on the grounds that the consumers are very sophisticated, and can make your their own choices in the marketplace. It was certainly not intentional but he could have done consumerism no greater service. What was noticeable about these extremists is that they are also lightweights, rank amateurs at the business of government. They happened to agree with Reagan, and he was beguiled by what they said, not what they did. It is possible he cannot tell the difference. |