This article appeared in the Weekend Australian Review Section January 6-7 1996 p1-2

Watching the world go round

|

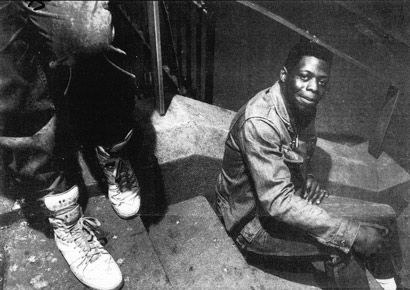

There are more than 4 million homeless in the US. In New York, thousands room the streets. One of them, Ernest Stevens, says his life could have been worse. The long line of homeless people on East 44th Street in Manhattan upset the office workers scurrying past. Glancing sidelong at a scene that invoked the spectres of middle-class life, they saw restless young blacks, defeated-looking Latins and old derelicts, bundled up in rags. "Welcome to St Agnes," muttered Ernest Stevens, springing from the van that had just drawn up, loaded with crates of food."Let's hope we don't have a riot in there..." The grimy old building on 44th Street was a parochial high school. Since the start of the year, when the cops began chasing the homeless from Grand Central Station, around the corner, the building has been used as a drop-in centre. The place isn't officially a shelter, and as a result, the 400 or so people who stay for the night are not allowed to stretch out. Instead they sleep, if they can, sitting up in chairs. "I hear if you really smart," said Mr Stevens, "you can get two chairs… If you lucky, you can, like, find a spot next to people that shower."Mr Stevens, 29, has been homeless for six years. He's slept in subway stations and in jail cells. He's woken up, after nodding off on the train, to find himself surrounded by teenage hoods."Yeah, they were black. They were brothers," he pulled a wry face, "probably out of Brooklyn. That's where all those punks come from. I like to think that's where they come from. In the melee, I didn't stop to ask them, hey, where you guys live, by the way." Mr Stevens and I struck up and acquaintance last year, when I got about a bit with some of the volunteers in a food program run by the Coalition for the Homeless. Now and then, he disappeared for a few days. Reappearing, once, with a few bruises and a cut over his eye, he said he had been shoved around by the cops. He didn't sound surprised: indigent blacks expect to get roughed up by the police, even if they've just been arrested for jumping a subway turnstile. For all the precariousness of his existence, Mr Stevens sees its deprivation in a different light. "It's boring," he said, looking embarrassed, when I asked if I could write about a day in his life, "it's really boring." Somewhere between 60,000 and 80,000 people in new York city are said to be homeless. Thirty thousand are in shelters. Thousands of others roam the streets, lounging on street corners mumbling to themselves or retreating to the subway; indeed, every train has its contingent of vagrants wandering down the aisles, asking for spare change. Significant numbers of homeless people started appearing in New York in the 70s (after patients were tipped out of psychiatric hospitals and left to fend for themselves); but homelessness did not reach epidemic proportions until the late 80s, when the rent for a small apartment in a drug-infested neighbourhood might be $550 or $600 a month-two or three times what it was in 1981 (though the minimum wage, $3.35 and hour, hadn't gone up a cent). |

Something of the sort happened in every big city in America, and if there am now upwards of four million homeless in the nation (as the organisations set up to assist themcontend), Ronald Reagan and his lieutenants are partly to blame. The people who ran Reagan's Department of housing lined their own pockets, but what they stole was a pittance compared with what they slashed from the federal housing budget, reduced from $US32 billion in 1980 two $7 billion this year.

Little colonies of people living in cardboard boxes have sprung up throughout the city in the past few years

Nowhere is the result more evident than in New York, the acropolis of private affluence and public squalor. Little colonies of people living in cardboard boxes have a sprung up throughout the city in the past few years. Hundreds of them are camped in and around the city bus terminal-making its underground floor a chamber of horrors where one might see cadaverous figures crawling out of piles of cardboard and trash. If they're more or less lucid and willing to talk, however, they may say they stay in the terminal ( or in a box in a deserted doorway or in the ice-cold caves under the Brooklyn Bridge) because anything at all is better than the city's public shelters, where they expect to be terrorised by a crazed crack addict. Ernest Stevens fails to conform to this feverish image. He isn't violent. He doesn't snatch old ladies' handbags because he is desperate for a hit of crack. Instead he used to wait until payday, squander every last cent on crack and vanish for a day or two. When we first met, last year, he had a job making the sandwiches the Coalition for the Homeless gives out at night. "I got $444 every two weeks. That's the kind of money people kill for. It was $7 an hour. Most day ever made before was$6.." He worked as a casual and managed to get himself fired the week he was to be put on the permanent payroll because he had vanished once too often, after a blow-out on crack. "I gave it (crack) up six weeks ago," he told me, "I'm pretty sure I got it beat now." These days, he gets $60 a week, less $5 tax, "to coordinate the food line at St Agnes..."He collected two weeks pay the morning I was following him around. The day would drag less than usual, he said, because there were chores he put off until he had some cash. "Why don't you get a full-time job?" I said, forgetting that I was supposed to be interviewing him, instead of nagging. We had stopped for breakfast in a mid-town diner; shortly before 11, the place was full of old people starved of company, and an old black woman, in the booth across the aisle, had tuned into our conversation. |

Mr Stevens was telling me about one of his stints as a security guard for a petrol station in Spanish Harlem, a district swarming with crack-heads. When a car pulled up, they rushed over to wash the windows or pump petrol, in the hope of a tip. "My job was to keep these people away from the cars," said Mr Stevens, who quit when several of them went after him, late one night. "You looking fo a job?" the sweet-faced old lady opposite piped up. "I heard the libraries are hiring custodians. And you could try the hospitals..." "Yes, ma'am," said Mr Stevens, docile as a lamb. The first chore of the day was his laundry. Emerging from the subway at East 96th Street, the border between the rich and the poor, he bought a $2.99 watch before collecting his clothes from the basement of a building used by the Coalition. He took a bagful to a nearby laundromat, tossed the clothes into a washing machine and declared that it was time for a drink.

'Why don't you get a full-time job?' I said, forgetting that I was supposed to be interviewing him, instead of nagging

The middle-class whites in Hanratty's, a bar around the corner, didn't give him a second glance. Mr Stevens, who usually looks neat, was in cotton pants, a jersey and a denim jacket. A dirty Green baseball cap was jammed on his is. Instead of sneakers, he wore thick-soled,shiny patent leather shoes. Sometimes, he said, he spent the night at the Bowling Green subway station, near Wall Street. "The police don't bother me. I've got these shoes on, and a long coat. The cops figure I'm, like, a stockbroker that went to a bar and got wasted, chillin' out on a bench 'til I got to go to work in the morning..."

I hadn't realised that his conceptions of middle-class life was so vague. It was as if he were from another country, not another part of the city. He was raised in a crumbling neighbourhood in the Bronx. His father fled when Mr Stevens and his brother were small. His mother, who worked a double shift at the post office, came home at one in the morning. "If the house wasn't clean enough, she would beat us." It could have been worse, he said. "... If I had to take it all in one lump, I'd say that I had a better life than most of the kids around here. Most of my friends' families were, like, on welfare." I asked what had happened to the others. "Lots of them are stick-up artists. Some are drug addicts. There's a few I like to think have made it, but I don't know, because they moved away..." |

Before finishing high school, he left home to enlist. Discharged from the army in 1981, he found work as a messenger and rented a small apartment in Spanish Harlem. "That's when I was happiest. I'd come home and have a joint and beer." He's taste's have got more expensive. If he has cash, Mr Stevens drinks Absolut vodka: with two shots under his belt, he strolled back around the corner ,bundled his clothes into a dryer and settled down to wait, in a grim little concrete park on the median strip."I really gotten a lot done," he said."Bought a watch, solved my time problem; washing clothes that be good for two weeks..." For a moment I thought he was joking. It was after two. Half the day was gone, and we were still cooling our heels near the laundromat. "If it wasn't payday," he said, in all seriousness, "I'd probably be hanging around wishing I was waiting on my laundry." Mr Stevens started using crack in 1984. It wasn't long before he lost his apartment. His possessions disappeared and his life disintegrated. He has drifted around For so long, in limbo, it's as if he can't imagine any other existence. Back at the Coalition office, at half past three, he put on clean clothes and hung about until he went off, close to five, to find a barber. "When I get my haircut," he said, "I've run out of things to do." At a quarter-to-seven, the van was loaded with food and we drove to St Agnes. The scene was as demoralising as usual. Sick, neglected old men and women sat like automatons. Young men hurled abuse at each other. A couple of crack addicts fought over a bread roll and, as usual, people who arrived after all the food had been handed out accused the volunteers of stealing it. Things quietened down, after an hour, but picked up again. At midnight-the curfew-when we return to St Agnes, a drunk who had just tumbled downstairs, lay on the first-floor landing with his head covered in blood. Upstairs, in a room with a faulty television set turned up loud, 50 or 60 people lounged, half-awake or half-asleep in school chairs attached to desks. "You have got to get out of here," I told Mr Stevens, appalled. "You have to get a job..." He couldn't get much of a job, he said. "People like me-the people you see here in St Agnes-all got bench warrants out for them. "You can't get a job where they check you out. All you can get is messenger jobs. At the minimum wage." He suddenly smiled and proceeded to a story that sounded a bit unlikely. "I was a messenger one time and a guy gave me 18 hundred-dollar bills to pay rent on a building. I'm saying, well, yo, if I was like, anybody else... I got friends who'd be on their way to Bermuda or Newburgh... $1800! That's enough for some people to start a new life." But not him, he said. "You got $1800 that don't belong to you. You got people looking for you. You in trouble if you have to find a job. "But most people don't think that far ahead, you know."

Several weeks later, Ernest Stevens smoked crack again. He has since entered a drug program. |