This article appeared in The Sun-Herald 2 January 1994. Mr Carr was not pleased with it.

Carr: as I was saying . . .

The first thing Bob Carr decided to do was to take me on stour of his office in Parliament House. He pointed out the originals of illustrations that had appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald, then drew my attention to an aerial perspective drawing of high rises in midtown Manhattan and a German Exressionist poster. Even before we sat down and I noted the things on his desk, from the pile of books - "improving literature people sent me" - to the Royal Shakespeare Company mug, I might have said that if the man were some of the parts he had on show, he was determined for the world to know he was an intellectual. Indeed, in the NSW Parliament, where politicians with bookcases full of real books (instead of legal tomes) are suspected of being susceptible to deep thought, Carr may be the only person in the position to parade the fact that he enrolled, last year, in a Workers' Educational Association course on Roman history. But he hadn't told me about it yet. Instead he was still up on his feet, talking about several other treasured possessions - cartoons of himself and the then-Premier Nick Greiner which had appeared before and after the election in 1991. At the time Carr, who had been the Opposition Leader for three year, campaigned like a man possessed, managed to surprise everybody, not least himself (though he seems to have forgotten that bit) by only just losing an election he was tipped to lose by a landslide. It assured him of the leadership position, for the time being. But two-and-three-quarter years is an eternity in politics. Carr's standing in the polls dropped after the Federal Budget last August, fell further with the news of Sydney's success in the Olympic bid and has failed to improve, even now. Though the Government is confronted with the HomeFund mess, contending with a hung Parliament and contriving to dispel the euphoria about the Olympics in the in-fighting over the spoils, the polls suggest that for the moment more people continue to believe that John Fahey makes a better Premier than Bob Carr would. In the past few weeks, Carr has had to fend off rumours about threats to his leadership. It didn't seem to make him any more receptive to the question I asked about it. In the blink of an eye, he managed to convey wordless astonishment that anybody could ask such a thing, and wordless annoyance at being forced to issue a denial. It looked as if he were about to berate me, but he pushed himself back in his chair, and with an air of suppressed impatience that almost succeeded in making me feel I'd been unfair to him, said: "It just can't happen under the party rules." The rules say the leader may not be removed except by agreement at the ALP's annual conference, but he had mentioned the rules only to dismiss them. "It wouldn't happen even if it could," he said. A restless man whose only known vice is an addiction to exercise, Carr isn't somebody his colleagues in the parliamentary party always warm to, and there are those who'll complain that his attention wanders as soon as they have said several words to him. |

|

But it hadn't escaped Carr that I had neglected what he was saying for a moment and he responded by putting the spool back on the sprocket and running it past again at twice the speed. "CBD . . . redevelopment . . . South Sydney . . . renewal . . . Walsh Bay . . . bit-sized chunks . . . " Then it was back to Fahey. "If I were Premier, I'd want to know why they weren't happening. I'd be trying to cajole the private sector into making them happen. This is what ought to be going on here . . . "I've got a view that NSW ought to be providing serious leadership, ought to be contributing to the national agenda. There's a range of things, like our anti-violence package. I'd like to give you a copy of that." Suddenly reminded that it was at his insistence that the ALP's latter-day education policy contained clauses on discipline and "standards" that hark back to the discipline and standards of the State school system of the 1950s, I remarked that his ideas on the subject seemed out-of-touch. On other occasions that the question of "standards" has come up, Carr, sounding more conservative than many of the conservatives who happen to be in government, has made approving remarks about school uniforms and "proper leather shoes". Now, however, he was talking about saving the schools. "The alternative is to see the State school system discredited by degrees and I won't do that - I won't see that done," he said. "I've probably been to more schools than any other State Opposition Leader. I mean I'm engaged in this debate - and I'll take you line by line through our policy." He looked please, almost as if he'd pictured himself at his best, conveying something, line by line, and when we were in the car again, I asked him what gave him real pleasure at the end of the day. He said he would have to talk about work. "When you have a win in politics, winning a by-election, selling your case in the media, pulling off a good interview on radio or Quentin Dempster . . . "That's the essence of politics - the reaching out with a message and scoring some empathy," said Carr. We had arrived at the scene of his first function for the evening, a Federal Department of Immigration reception for the representatives of ethnic organisations, held at the department's new city offices, in a building near Central Station. Carr, the only State or Federal politician present, was met at the entrance. But he still seemed to be reviewing the answer to the last question. He wanted to change the emphasis. "I enjoy the whole political process - not just the communication," he told me, as his footsteps echoed through the over-imposing lobby of the Immigration building. "The clash of ideas and interests - that's the essence of politics. And the impact you have when you adhere to a policy. I'll just give you one example," he said. But the lift doors swung open at that very moment, and much to my amazement, he forgot. |

|

|

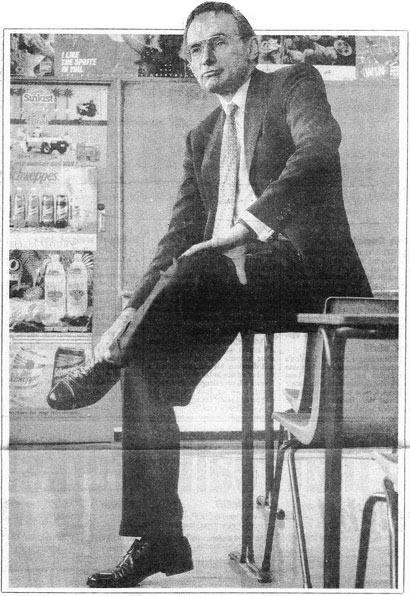

I was to notice a different phenomenon. When he was quiet, the face behind the big spectacles seemed to close down, as if his nose were moving towards the cleft in his chin. His face became alive again when he spoke, whether or not he was uttering a fragment of a speech he had uttered countless times in the past. Politicians all repeat lines so often that observers of the process also run the risk of repeating themselves, likening the process to something mechanical such as the random play function on a CD player; even Carr, a good speaker with a fine modulated voice, seemed to shuffle the phrases at random more and more rapidly throughout the evening until one was tempted to imagine him suddenly sitting bolt upright in bed in the middle of the night, saying: "Fahey's asleep on the job . . . " "John Fahey's asleep on the job," Mr Carr told me the first time, at the very moment he had seated himself in the back room of a Darlinghurst cafe. Carr, 46, a former journalist who makes a point of being available to the press, had instructed me to tag along when he went for a bite to eat. He is famous for not driving, but as Leader of the Opposition naturally has a chauffeur-driven government sedan. In the car, he had a go at Fahey, said something nice about Jeffrey Kennett and Wayne Goss and mentioned a scheme of his own "for a burst of building activity in the CBD - for high rise residential development like the better parts of Manhattan. "By cutting land tax, by identifying precincts suitable for rezoning and bringing forward an industrial relations package that assists building in the CBD, we can get things moving." |

He had grown expansive, the lines of his face softening as he reeled the familiar phrases about "precincts suitable for rezoning" and "model urban renewal". It did not seem to be the moment to ask what kind of industrial relations package he had in mind. The Opposition Leader, who regularly appears to stand to the right of his own right-wing faction, does not identify strongly - if at all - with the Labor Party traditions he tells journalists he loved reading about as a lad; a year ago he turned up at the rally in Sydney called to protest against the industrial policies of the Kennett Government and told off the workers who were there, describing them as "extremists". I tried to ask him about his "industrial relations package" any way but he waved the question away for he wanted to mention another of his proposals, "that the State Government intervene to redevelop industrial sites in South Sydney". The car stopped. We were at a Stanley Street cafe, a haunt of the body builders from the gym around the corner, one of whom, a person the size of Arnold Schwarzenegger, caught my eye because it was so difficult to guess the, uh, primary gender. If Carr had noticed he gave no sign. He was marching through the cafe, still talking about "redevelopment" and had no sooner dropped into a chair and uttered the line about Fahey, asleep on the job, than he was back to "modern urban renewal", and the revamping of one place or another in "bite-sized chunks". My attention had drifted. Because I happened to have interviewed Kennett one week and Carr the next, I was wondering how many politicians were so remote from the ordinary run of humanity that almost the first thing you would like to ask them – not that you dared, of course – was if they ever felt really at home with themselves. | ||