This article appeared in The Australian 13-14 May 1995

Slaves to Fashion

Some of Australia's most glamorous labels swing of skirts, dresses, vests and jackets sewn painstaking– and painfully – by men and women earning just a few dollars an hour. Elizabeth Wynhausen investigates Should this be happening in Australia? Binh Ngo is seated at sewing machine in her Melbourne garage, the make-shift workroom where she spends more than half her life. One of the growing army of outworkers producing Australian-made clothes in conditions more readily associated with sweated labour in the developing world, Binh Ngp* (asterisks indicate pseudonyms), a broad-cheeked, watchful woman in her 30's, is at work here in the garage concealed by her Footscray house. She works 14 hours a day, seven days a week. But if there is a rush order or a big job, she works through the night, the everyday feeling of loneliness sharper than the pain from her reddened, swollen hands. It seems they could now be Over 300,000 outworkers in the clothing industry in Australia, more than half, like NGO, Vietnamese. These days most garments made in Australia are made in private homes. Major clothing manufacturers have closed their factories in the past five years, handing production over to contractors who rely on a vast, unregulated labour force made up of immigrants, often pay as little as $2 an hour. Indeed, in a country that once prided itself on the fairness of it's labour market, the effects of deregulation on the clothing industry may give a foretaste of Australia's industrial scene in a few years. Its investigation of the industry, the Textile, Clothing and Footwear Union of Australia has found that outworkers, paid about a third of the award rate, are making expensive designer clothes which sell in many of the countries leading retailers. Companies as high-profile as Jag, Perrin Cutten, Laura Ashley, Ken Done's Done Art and Design, George Gross, Anthea Crawford, Adidas and Country Road were among those named in federal Parliament last month after the unions report,The Hidden Cost of Fashion, exposed the disgraceful conditions in our "invisible clothing industry". In some cases recorded by the union, children as young as eight worked at sewing machines beside their parents until late at night, the whole family caught up in the desperate struggle to deliver the garments by a certain date. These deadlines can give a nightmarish urgency to the endless drudgery of their lives, for they aren't paid – and may be fined – for work delivered late, part of a pattern of exploitation one step up from slave labour. Fearful outworkers who contacted the Textile, Clothing and FootwearUnion during a nationwide, two-month-long phone-in held last year spoke of being intimidated by the operators of the smaller clothing firms, the contractors who cut the garments, give out the work and do the finishing touches. Sometimes, says Barry Tubner, assistant secretary of the NSW branch of the union, the outworkers are told that unless they sign up for unemployment benefits – and cheat on their taxes, of course – they won't get any work at all from the subcontractorse, immigrants from the same country, if not the same province, as themselves. Several years ago the Australian Tax Office found that the rag trade's black economy cost more than $100 million a year in lost revenue. The Tax Office has devised an ambitious scheme to monitor cash payments, but there have been many such schemes before. According to the union, what the outworkers who fudge their incomes want is a chance to enter the formal economy without being penalised for past breaches. Until that happens, says Tubner, the contractors have a hold on them "and it's very hard for them to get out of that trap". |

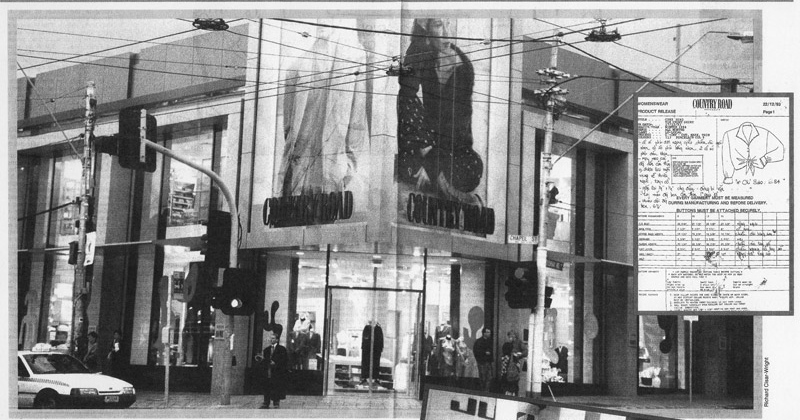

But things are much better for outworkers like Binh Ngo though, as she says, giving her real name, she pays her taxes and hasn't anything to fear. NGO, who was a doctor in Vietnam, began sewing at home alone a month after she came to Australia in 1987 with her husband and five-year-old son. They have two children now and are paying off the mortgage of a small, brick house where Ngo spends less time than she does in the garage. Such backyard workrooms are often alike, it seems, with a hammock for the small children, a video, a big TV and a portable stove, as if much of life has been reduced to the few components set in arms reach of the Juka brand sewing machine. The decoration often consists of photographs of glamorous-looking women, torn from the pages of Vietnamese magazines. But NGO has adorned the wall of her work room with her own chronicle – a strip of white material decorated with the labels of some of the garments she has made, the labels from chain-store clothes surrounded by labels from David Lawrence and Country Road. Towards the end of the interview, in fact, she produces a sheaf of specifications for the orders of shirts, vests and coats for Country Road, the spotless bits of paper like a record of the passing years. Ngo seems to take care with things, even with the cheap furry toys, yellow as pork fat or pink as fairy floss, that have been hung on hooks, like ornaments. The attempt to brighten up the place appears all the more for forlorn as one listens to her tell her story, and the endless sewing comes to seem like a metaphor for the endless misery of an outworker's life. Her husband, a machine operator, works long hours. They seldom talk because NGO is at her machine until two in the morning, hearing only its hum and the ticking of the big wall clock, sounds that compound her aching loneliness. In the daytime her one companion is her daughter, three, who plays in the dusty, lint-filled atmosphere of the garage, until your son, now 13, comes home from school. "There is no one to talk to," she says, asked to describe what life in Australia is like. She speaks in Vietnamese, translated by Hung Nguyen from the Clothing and Footwear Union's Victorian branch, and as Nguyen has predicted, keeps working while she talks. The men's lined vests that she is making at the moment for the Ojay company label Moods will be sold retail for $129, which is $120 more than the $9 Ngo will get for each. The work is harder going than she had hoped because the fabric is stiff and, as she tugs it this way and that, the inflamed-looking skin on her fingers almost seems to crack. Ngo doesn't mention it of her own accord. The symptoms of overuse syndrome (as repetitive strain injury has been renamed) are common among the outworkers, at their sewing machines more than 12 hours a day. Hang Phuong* another of the outworkers Nguyen takes me to meet, is a doll-sized woman of 38, unable to straighten out her hands. Both Phuong's hands were operated on last year because they had curled up like claws. The surgeon said he mightn't be able to do much about it the next time. The clothing industry relied on outworkers, of course, even before the gradual removal of industry protection – the centrepiece of the government's Textile, Clothing and Footwear Industry's Development Plan – cost tens of thousands of garment-industry workers their jobs. Seven years ago, when Binh Ngo hadn't been in Australia for long, she could average $700 per week. Ngo is so skilled that her contractor always gives her work. But piece rates have kept falling and nowadays with luck, she makes about $450 for the same 98-hour week. | So many factories in the regulated sector of the industry have closed down and so much of the production has shifted to the smaller clothing firms that the union's report suggests that outworkers now outnumber the workers left in clothing factories by about 14 to one. There are hold-outs. Nif-Naf, which manufactures jeans, denim shirts and jackets, is one. "We don't use outside workers because the quality of the work's not good enough and the delivery is unreliable," says George Koulloupas, the company's general manager. Though other label companies may say they used outworkers because it costs them less than making the clothes themselves, Koulloupas says that, " with jeans manufacturing, it isn't dearer to do the work inside. "We're all set up with the five or six machines required for manufacturing jeans and other denim products. But for other clothes, maybe it's cheaper to use outworkers." Other clothing companies have sold off everything but their cutting equipment, if they've even kept that. In place of the large factories, there are small ones, hard to spot behind the curtained-off shopfronts in the Springvale, Victoria or Cabramatta, NSW, and harder still to regulate. At the first hint that the authorities are investigating them, the fly-by-night operators will vanish in the blink of an eye, one element of a situation more than likely to keep outworkers stressed out. "They really don't have a choice about when or how they work," says Annie Delaney, the outwork co-ordinator from the Victorian branch of the textile union, a co-author of the union's report. Though outworkers are tied in with a particular contractor, often the only connection that non-English-speaking migrants not long in the country have in the outside world (and so a contact they may need to feel has meaning), "the relationship is tenuous," in Delaney's words. There isn't any holiday pay or sick leave, let alone loadings or superannuation. Before they get work, they may have to sign documents declaring themselves bona-fide subcontractors, responsible for their own tax and Workcare cover. Not only are they supposed to be paying their own taxes, they have to buy and maintain their sewing machines, all for the piecework equivalent of an average $2.50 an hour before tax. And yet, says Delaney, "they feel that the only way to keep getting a supply of work and have at least a reasonable relationship with the contractor is to do whatever they're asked. They work when they're required to work and finish when they're required to finish, though it might mean staying up all night." Hang Phuong's husband, Tran*, applied for numerous jobs, to no avail; now he works with her in the Melbourne garage behind a high, wrought-iron gate. Outside the garage is a vegetable garden they tend if there's a moment to spare. But on the day we meet, both are so numb with exhaustion that it costs them an effort to speak. For three nights running, they have had three or four hours sleep. Behind schedule on a large order of corduroy children's dresses for which their contractor is giving them $3.70 dress (which works out about $2.50 an hour before tax), Hang, her anxiety palpable, says she will have to stay up all night. No one thinks to say anything about her crippled hands; instead the thought of the deadline, a week away, looms over every minute of the day. Behind clothes doors: Country Road is among the high profile companies named in federal Parliament last month after a union report exposed the appalling conditions in the clothing industry, in which migrants, work for long hours and little money to precise instructions. |

Working until late at night, with the whole family joining in, they make $500 to $600 a week. The couple have four children, all girls. At times like this the three eldest, 11 to 18, help out with the work, joining their parents to stop to sew all weekend and for three hours after school. The baby of the family, who is two, clambers up to snuggle in her mother's lap for a few minutes that the sewing stops as we talk. And then Hung Nguyen, anxious for them in her turn, says that we must leave so they can go back to work. Why working for another company two years ago, Hang Phuong took back order because she was ill, and the contractor refused to pay the $3000 owed her and her husband for the previous two months' work. The union is trying to sort it out. But more often than not, outworkers have to ask again and again for the money they're owed; seldom do they feel themselves in a strong enough position to refuse to do more until they are paid. "What was really clear from the phone-in was that there is this wall of fear," says Annie Delaney. "We've spoken to very many women who kept working for a contractor that hasn't paid them. "The women don't have a lot of networks or links outside. They want to hang on to the one they've got." But even if they've gone out of their way to placate the contractor, she says, "they often get done over really badly. "It's quite common for the businesses to change names overnight. They're being paid by X company and they're paid every few weeks," Delaney says, "then that company suddenly gets a new name and new directors – probably other family members. The company is in the same premises with the same machines. But the outworkers are told they can't be paid because X company's bankrupt. "The other thing that's common is that the outworkers notice a mistake in the cutting and ring the contractor, he says 'sew it up anyway and it'll be okay': then they return the finished work and are told 'there's a mistake, we can't pay you'. Or they're told, 'there's a problem with the quality and we had to fix it up'. Maybe they were getting a few dollars a piece, but they're charged $10 a piece for repairs." Many at too frightened to complain about the rip-offs, fearing they'll be reported because the contractors have insisted they sign up for unemployment benefits before they get any work. "The other thing that happens, which quite a lot of people have talked to me about in the past few months," Delaney says, "is that when they ask for a pay increase, thy'ere told to apply for the benefits. They're instructed to say, 'I'm working for this contractor two hours per week' – or whatever it is that won't put them over the limit – and the contractor tells them he'll support the application." In fact, she contends, some of these contractors regard unemployment benefits as a sort of wage subsidy, even a safety net when there isn't much work to give out. If it comes to that, the contractors themselves may make only a modest profit, whether they are supplying the high-volume chainstores or the likes of Laura Ashley, Jag and Country Road. There used to be a clear line between them. Not now. |

In his house in the Melbourne suburb of Sunshine, Duct Tranh*, and open-faced Vietnamese man of 35, produces sample shirts and jackets for Jag Jeans. Tranh, who used to be a hospital cleaner and speaks a little English, now works at home with his wife. That they get more a piece then the average, considering the renowned Jag label they get less than you might expect. For a lined, denim children's jacket that is double stitched and took about 2 1/2 hours to make, they were paid $11 a piece. For a denim shirt with a suede collar, and much double and triple stitching, they get $8 (which came $3.90 an hour). The shit retails for more than $100, but it does have a patch with the message, "Jag jeans. It's another way of life". So it seems. To distance themselves from the exploitation of outworkers, retailers claim that they can't do much, if anything, about the situation. When he is asked about the amount quoted above, Eddie Chua, the general manager of the Palmer Corporation, the company that owns the Jag Jeans label, says, "the questions should be directed more to the contractors than to us – we've got no control". "It's none of our business," says Tim Rumble, the financial controller for Laura Ashley. "This slave labour – call it what you like – there's not much control that Laura Ashley has. "Most of the factories have their own workers – how far down the track do you go to make sure of what's going on?" "We try to take the necessary safeguards," says Rod Shield, the general manager of Ojay Pty Ltd, a retailer with 18 stores around the country, "but what the contractor does is outside our control." Like executives of other retail companies, he's inclined to suggest that the Vietnamese owners of the small family-operated factories are "not too badly off". In reality, says Annie Delaney, whose work often takes her to factories like that, "smaller contractors tell us the price they get...makes it impossible for them to pay award rates and still operate the business". "At the end of the day," Laura Ashley's Tim Rumble finally says, "if you want to be competitive, you go to the people who give you the best price." That's how the system is structured, in fact. "On a Friday afternoon," says Barry Tubner, from the NSW branch of the union, "they [the fashion houses] get between 10 and 50 contractors and have a Dutch auction. They'll say, 'who can produce this garment for $14', and go down until one factory says it can make it for six dollars." Watch the same effect may be achieved if the larger retailers negotiate directly with a couple of manufacturers competing for their work. The owners of one of the manufacturers for Country Road told Delaney that they were getting $21 a piece from the company for woollen vests that it took their outworkers two hours to make. Country Road pays its manufacturers about the best prices in Melbourne, it seems. Yet of the $21, for a garment expected to sell retail for $150, the factory made a profit of $2, Delaney says, and the outworkers received $9 (just under half the award payment for two hours work). |

After Country Road was among those named in Parliament, Mike Howell, the chief executive officer of Country Road, vowed that his company wouldn't deal with suppliers who failed to meet its standards or observe the relevant industrial awards. Indeed, Anna Booth, the Textile Clothing and Footwear Union's and national secretary, says that "both Country Road and Sportscraft have agreed to work with the union to develop a scheme to make sure that they're not exploiting outworkers". This rhetoric is all very well, but will it mean better piece rates for contractors? Booth isn't sure. Telephone by The Weekend Australian, Howell is asked how he responds to the revelation that, at $21 a vest, at least one of Country Road's regular contractors wasn't given enough per garment to pay anything resembling decent rates. "I'm surprised by that," says Howell of the figure, suggesting, "the alternative is for for the manufacturer to say to us 'that's not enough'". But surely Country Road would no doubt go straight to the next manufacturer on its list? "At the end of the day, we're looking at the retail price," says Howell. "We've got to be responsible in the total sense." But that still leaves the outworkers getting $9 of vest. Outworkers seldom make the"total garment", Howell says, the first time we talk. The next time, he says he has asked his production people, who've told him that it would take 60 or 65 minutes rather than the two hours both the contractor and the unions Annie Delaney, not to mention Binh Ngo, say that it takes to make the vest. "I can't believe it," Howell replies. "Sure as God made little apples, they're putting some fat on that." In Footscray, Binh Ngo is riffling through her sheaf of Country Road's specifications, telling Nguyen, who translates, that doing the work for this company always demands great care." "They give you the measure – how many centimetres for this, how many centimetres for that", she says. But her own precision is evident a sheep reels off piece rates and prices, pausing to exclaim over the specs for a crinkle blouse in a fabric so difficult to manage that, at $4.50 a piece, she only made about $150 all that week. The blouse sold for $90 last winter, says Ngo, who is well aware of the retail prices for the garments that she makes because the factory, which does the finishing, attaches to swing tags to clothes, delivered ready to hang in the shops. Only last November, she made 130 men's winter coats for Country Road, for which she received $10 each. "That coat would be $100 in the shop," Hung Nguyen volunteers. "Hundreds," Ngo sees firmly, in English. * The names of the outworkers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them and their livelihood. |