This article appeared in The Australian Magazine 20-21 June 1998

End of the road

|

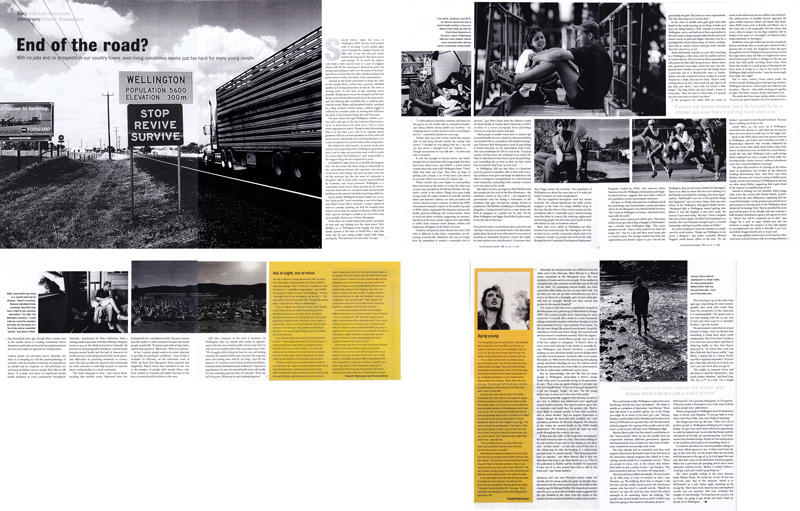

With no jobs and no prospects in our country towns, even living sometimes seems just too hard for many young people. Shortly before 8, the town of Wellington, NSW has the fresh-washed look of mourning. A pure golden light pours through the camphor laurels and silky oats in the fine old park which borders the main street. The street curves and swoops. To its north the baker's wife feeds a little minced meat to the magpies whose trills fill the morning air. Beyond the park, the young man pushing a roller over the grass of the bowling club is so intent that the roller and the bowling club green seem to define the limits of his consciousness. Instead of the hustle and bustle of urban life, with so few people about, actions have a precise, chiseled quality as if etching themselves on the air. The town is rousing itself. At this time of day anything seems possible. Shopkeepers sweep the footpath and the first sleepy-eyed school children head down the main street, past the Hitching Rail and Ballet Bar, a clothing store with the words “Ballet and Eisteddfod Outfits” inscribed on a shop window. Further along a solitary jogger is reflected in a window under an awning that still bears the name of the Colonial Donut Bar and Tea Rooms. The past echoes through Wellington, settled a century and a half ago; to this day Cameron Park bestows an air of distinction on the main street. This is a town where appearances matter. Though nearby Burrendong Damn is at less than 3 per cent of its capacity; proud gardeners still turn on fixed sprinklers as if the water will never run out. meanwhile, the council spends $900 000 a year to maintain local sports fields, parks and gardens. But behind its solid facades, its picture-book park and its outward gentility; life in Wellington (population 5600) can be edgy and uncertain. Most of all for youth in a town where the building of a new supermarket is the biggest thing that has happened in years. | It wouldn't be right, however, to say little else happens here. On the surface, life flows along as unhurriedly as the conversations between the customers and owners of the local coffee shops who pick up where they left off the previous day. But the sense of continuity is deceptive. Like so many other country towns, buffeted by economic and social pressures Wellington is a community under stress. Some say they see its effects from the times GPs are consulted about mental health problems to the extent of alcoholism and drug addiction. Every month Wellington hospital 13,000 free “party packs” (each containing 10 one ml syringes) says Sister Louise Kitch, formerly a senior registered nurse in casualty, pointing out that the hospital does what it can to stop the spread of diseases. Still and all that’s 130,000 syringes a month in an area with some 9000 people, about 1000 Aborigines. From where he stands behind his perfect pyramids of fruit and veg, looking over the main street, Nick Birbiles, 30, of Wellington Fruit Supply, the shop his family opened at the time of WWI, says that every day he sees young people dazed with drugs passing by: “The kids here are lost souls,” he says. “I could walk you round the cemetery and show you the graves of a lot of kids who’ve committed suicide,” says Alison Triffett, whose middle son, Geoffrey – an outgoing man of 27 who seemed to have everything to live for – committed suicide two years ago. Triffett, who was close to him found him minutes after he had hung himself outside the cottage they shared. “I thought he was joking with me. I thought he’d say ‘tricked ya’…” Though unconscious, he was still alive – he died soon after in hospital. If ever she thought of suicide before, she hadn’t thought of it in connection with young people, but there have been others since, says Triffett, a warm, hearty woman who is the cook at the Wellington Hotel. “I don’t think they have any hope. They have no hope of getting a job, a house, a car. If they have a job, there’s no security. There’s no security for anyone now…” | Where suicide rates were higher in metropolitan than rural areas in the sixties, it is now the other way around, says psychiatrist Dr Michael Dudley, who has made a study of the subject. Things have gone badly wrong under the calmer surfaces of rural life. Alcohol abuse and domestic violence are more prevalent and chronic disease is more common. In March the NSW government released a report on the health of young people in NSW which emphasized the disparity between the health, general wellbeing and socioeconomic status of rural and urban residents, suggesting for instance, that those in the more remote regions were more likely to suffer from coronary heart diseases, asthma and melanoma; all highest in the state’s far west. “Isolation and poverty have always been there. But what is different is that these communities are becoming economically redundant and may no longer have the population to sustain a reasonable level of services” says Peter Dunn from the Gilmore Centre for Rural Health at Charles Sturt University in NSW, co-editor of a recent monograph about psychology services in rural and remote Australia. “Most people in smaller towns have to travel to get mental health services, which are often provided by overworked GPs or counselors with limited training,” says Professor Bob Montgomery, head of psychology at Bond University on the Queensland Gold Coast, who runs workshops for GPs in rural areas. “A typical country GP has twice the workload of an urban GP. They’re often keen to learn how to provide psychological counseling but as soon as they see how much time is involved, they’ll say ‘we just cant…’” In Wellington, GPs say that there is a desperate need for general counselors able to deal with everyday problems from grief and family breakdown to the effects of long term unemployment in a hard-pressed rural community contending with constant revisions in its own place in the world. | Like others in town, greengrocer Nick Burbiles feels that people who live west of the Blue Mountains – the sandstone curtain as they call it – are forgotten by governments (and the feeling is forerunner to the sentiment that gets out – and – ratbags elected to parliament). But Burbiles is thinking of something else altogether. Casting himself back to a time before his birth, he images as a golden era, he says: “In the fifties Wellington was bigger than Dubbo [50 km away]. It was the hub of the west.” Wellington’s deputy Mayor, Mark Griggs mentions the “old days” and just as one harks back to the days when myths about the bush were still central to our sense of ourselves as Australians (however remote the reality for most quarter-acre suburbanites), it becomes clear that Griggs means the seventies. The population of Wellington was about the same then as it is today, but today’s residents are more marginalized. This has happened throughout rural and remote Australia. The cultural significance the wider society assigned to the bush was being whittled away at the time that the effects of the rural recession and the precipitous falls in commodity prices started tearing away the fabric of country life; reducing employment and forcing people who had taken great pride in their self reliance to rely on handouts instead. More than 2000 adults in Wellington get their income from social security. The aborigines who live in town (or in a nearby community which used to be a mission), include 105 people who work for the dole through the two Community Development Employment Programs, funded by ATSIC. One observer, Helen Hanslow from the Wellington Information and Neighbourhood Service, suggests that more than a third of the population receives government assistance. Life goes on. People shop and have weddings and all the usual things, says Tuna Sanders, suicide prevention officer for the Macquarie Area Mental Health Services. “But I look on Wellingto as beinga depressed town, especially for youth.” |

| Jobs are scarce, and scarcer still for girls. “They leave school at 15 to get a job at Bag-a-Bargain or McDonald’s,” says a teacher from Wellington High. “The career prospects are nil – they’re often sacked at 18, when the wages rise – but it’s a job and there aren’t many jobs in country towns. The average student has fairly low expectations and doesn’t expect to get a decent job, particularly the girls. They have no career expectations. The best they hop for is to have kids.” In the cities as middle-class girls grab with both hands the world opening up for then it looks as if boys are falling behind a little. Instead in towns like Wellington, one is cast back more than a generation to the time many ordinary people believed education was thrown away on girls and higher education was for a privileged few. Back in those days, of course, working-class kids in country towns could get work whether they left school at 15 or not. Alexia McDonald, a slender 20-year old, is lunching in a Wellingto coffee shop with her mother and her 16-month-old son. The two women tell an acquaintance who pauses by their table the good news. Alexia’s sister, who graduated from high school last year, has telephoned them, thrilled to report that she finally found a part-time job in a Woolworths store in Dubbo. Alexia, who also completed school, worked as a motel cleaner for a while then had her baby. “There’s really nothing else to do here. My friends my age, they’ve all got kids, just about. I wish I’d waited a little longer.” Not long before she had visited a friend in Newcastle. “Now I’ve been to Newcastle, it’s opened my eye even more to what’s out there.” | If the prospects for white kids are scant in Wellington, they are even more limited for Aborigines. There is so little for them that the local opening of a McDonalds’s was hailed for creating a few more opportunities. “McDonald’s was one of the greatest things that happened,” says Lee-Anne Daley, chief executive officer of the Wellington Aboriginal Health Service. “Aboriginal kids in Wellington started getting jobs. Before it was the hospital, if you were lucky; the council, if you were lucky,” she says. “I have a nephew who was school captain. He didn’t find anything for 12 months, then was fortunate enough to get a 12 –month traineeship with Sport and Recreating in Dubbo.” For others looking for work the situation is complicated by racial tension. “People say Wellington is not racist; I disagree,” says police constable Michael Hgggett, youth liaison officer in the area. “It’s not racist on the surface but you see a hell of a lot of hatred.” The undercurrent of hostility doesn’t approach the open conflict between whites and blacks that dominates NSW towns such as Bourke and Moree, nor is the crime rate at all comparable. But the crimes that occur, often in surges (so six shop windows will be broken in the space of a fortnight), are blamed rather indiscriminately on the Aborigines. Doubtless crime gets talked up because everybody knows everybody else; as racism gets confused with genuine fear of crime, the imaginary crime rate goes though the roof. In Wellington the process has reached the stage where some old folks are frightened to leave their homes to go to Dubbo or Mudgee for the day, and locals have held public meetings about crime. | Most blame the trouble on a small group of Aboriginal children, some as young as 12, who in the words of the Wellington High school teacher, “roam the streets night after night after night”. One of many country towns where public life revolves around drinking places and sporting activities, Wellington has about a dozen pubs and clubs but just one place – Maccas – where kids can hang out together at night. The Police Citizens youth Club shuts at six. The adults don’t have many options either, of course. “If you’re not sports-minded, you’d be inclined to be a drinker,” says motel owner Russell Gersbach, “because there’s nothing much else to do.” Louise Kitch, 34, who grew up in Wellingto, remembers her dismay as a girl when the last picture was torn down to make way for the rugby club. Back in the fifties there were two picture theatres in Wellington says barber and ex-bookie Leo Duff, a Runyonesque character who recently celebrated his 50th year in the same small, dusty barber shop. Duff, whose recollections were recorded for a local history, recalls the time that Wellington had a gold dredge which employed 100 men, a couple of flour mills, two freezing works, a butter factory, a railway refreshment room and a manual telephone exchange. The place still seemed to be thriving in the sixties when its population was swollen by the labourers building Burrendong Dam. And then, says Nick Birbiles, the town sort of went to sleep as Dubbo grew raplidly (much to the irritation of Wellington locals who are bitter about Dubbo, suggesting that it gets ahead a the expense of neighbouring towns). | Instead of looking over his shoulder, Mark Griggs (who owns the century-old Federal Hotel), projects himself into the next millennium, explaining that the council has bough a 200ha property just outside town and proposes to develop part as the Wellington Rural Industrial technology Park. They’ve installed the front grid and the gates. So far, though, only one company, a bulk fertiliser distribution agency, ahs agreed to move in. “about four will be will be employed out of that,” says Griggs. He is such an eager, affable man that one hesitates to weigh the prospect of four jobs against an unemployment rates which is officially 12 per cent, and which Griggs himself puts at 16 per cent. The same slightly wistful note is to be heard in other rural areas as local boosters talk o reviving industries that flourished years ago, though what a visitor sees in the smaller towns is a fading community where business and banks are boarded up and government services once taken for granted are closing down. Lurking behind the inevitable social pressures and what it is tempting to call the psychopathology of rural life, with its worship of firearms, its dependence on alcohol and its emphasis on self-sufficiency, are emotional problems country people don’t like to talk about. “It is fairly clear there are significant mental health problems in rural communities throughout Australia,” psychiatrist Dr Peter Yellowlees, then a visiting medical specialist at Broken Hill Base Hospital, wrote in 1992 in the Medical Journal of Australia. |

He pointed out that geographical isolation, rural attitudes towards mental health and the lack of resources of health services with inexperienced staff create particular difficulties in providing treatment in country areas. The other problems he reports is that rural people are often reluctant to seek help because of concerns about confidentiality in a small community. “The bush telegraph is alive,” says Louise Kitch, recalling that another nurse, depressed after her husband left her, committed suicide. The poor woman had felt unable to seek treatment because she feared people would talk. “If anyone gets hold of juicy information they spread it,” Kitch says. “There’s no privacy.” In fact, country people seem to be more reluctant to get help for psychiatric problems – even if help is available. In February, on the mid north coast of NSW, the local Port Macquarie News reported that magistrate Wayne Evans had remarked on the rise in the number of people with mental illness who were treated as criminals and joined, because of the lack of mental health facilities in the area. GPs’s also complain of the lack of facilities. In Wellington, they say anyone who wants an appointment with the area mental health service may have to wait up to six months unless they can conjure up a crisis. ”We struggle with it doing the best we can, not looking towards the mental health team, because the response time and waiting time will be too long, says Dr Ian Spencer. If “a patient with normal emotional problems, someone whose husband has just walked off” request an appointment, he says the mental health team will usually be busy assessing patients who are suicidal. “They say, we’ll ring you. Weeks go by and nothing happens.” The result in places like Wellington could not be more horrifying. Suicide has been normalized. “We think of suicide as a symptom of depression,” says Murray. “These kids talk about it as another option, of the the things you might do in future if you don’t get a job.” Murray, Sanders, youth worker Helen Handslow and teachers fro the local TAFE have set up what they call “the alterative schools program” for a group of the youths most at risk, seven 15 and 16-year-old boys from Wellington High. Murray likes to joke that the school’s contribution to this “intersectorial” effort (to use the modish term for cooperation between different government agencies and departments) was to hand over their most troublesome students for several days each week. The boys already feel so unwanted and have such negative ideas about themselves that in the first term of the alternative schools program they talked as if committing suicide would be a community service. “There are people in town, even at the school who believe these kids are just a waste of time,” says Sanders. “The kids themselves will say, ‘I’m better off being dead…’” One boy had been bullied mercilessly. “He was beaten up by other boys in front of teachers in class,” says Hanslow, 24. The bullying drove him to despair. I ask the boy, a stocky, croaky voiced 15-year-old, if he knows anyone who has tried to commit suicide. “Myself for starters,” he says. He tried last year, before the school managed to do something about the bullying. “The people from mental health services said if it didn't stop they’d be going to the board of education about it.” The school gave up on the other boys ages ago, suspending the most unmanageable ones week after week. Seen from the perspective of the classroom it is understandable. “We spend most of our time dealing with the 20 per cent of kids who don't want to or shouldn't be there” says the teacher. |

The government wants them in school because it helps create an illusion that something is being done about youth employment. But to the boys it looks as if no-one even notices them until they’re behaving badly, as they feel they’re expected to. “At school they treat you like a little kid, don't know nuffin’,”says Mitch a skinny kid in a Tazzie Devil’s cap who’s regularly suspended. “If you’ve got a bad name and you try to fix it, you can’t, you can’t fix it after you got it.” “You might sit someone down and ask them to describe themselves,” says youth worker Hanslow, “and they’ll say, ‘Oh I’m a c*** of a kid’, ‘I’m a stupid little bastard, ‘I’m a juvenile delinquent’, or ‘I’m psycho’. What they believe themselves to be is the sum of all the names people have called them.” Many young people in Wellington don’t let themselves hope or dream, says Hanslow. “If you get kids to write down what they’d like, they can’t think of anything.” But things may look up, she says. “There are a lot of positive people in Wellington working hard to improve things. I’ve got a boy who’s been offered an opportunity to walk the Kokoda trail. Local clubs like Rotary and the sub-branch of the RSL are sponsoring him. Local businesses have donated things. People are becoming aware of the problem and trying to do something about it.” It could be said there are several possible endings to this story. Mitch figures in one. A state ward from the age of four who first cut his wrists he was back with his parents at the age of 13, he tried again the next year. But after a year in the alternative schools program, Mitch ahs a part-time job pumping petrol an a more optimistic outlook on life. “before I coundn’t believe I could get a job and I ended up getting one.” The other possible ending to the story features lanky Nathan Smith. He works too; in fact he has two part-time jobs. But at the moment, Smith is at McDonald’s on a soft, balmy night, summing up his young life. There have been times he has contemplated suicide buy not anymore. Not now, certainly. Not tonight. It’s his birthday. “I’ve been here for 19 years. I’m 19 today. I’m going to get drunk and that’s what we mostly do in Wellington…”

EXTRA BIT AT THE END Naturally the situation looks very different from the other end of the telescope. Myra Murray is a clinical nurse consultant in the Macquarie area. The area includes 16 towns and 160,000 people. If she worked in a hospital she says, someone would take over at the end of her shift. “In community mental health, you drive somewhere like Cobar, you see a 15-year-old at risk. You do what you can, set up what networks you can, but if you’re not there for a fortnight, part of your mind asks, will that be enough? Should you have moved him 300km to the nearest hospital?” If it comes to that there isn’t a a psychiatric hospital in the Macquarie area; patients go to Bloomfild in Orange, NSW. But country people aren’t clamouring for more resources. “I recently did a study in a a rural community asking community members what they thought of as the most essential services,” says academic Peter Dunn. “Up the top were things like general practitioners, hospitals, ambulances, bricks and mortar things. But mental health services weren’t considered essential. That’s the stigma.” If you mention mental illness people may recoil, as if the very subject is contagious. “It doesn't affect us; we’ve never had anybody in the family be mentally ill,” says Wellington man Russell Gersbach, a youthful looking 40-year-old whose family owns the Bridge Motel and other local businesses. Gersbach talks as he washes the family car. With his two beautiful young kids playing nearby and birds wheeling out over the willows which droop into the stream, the scene is like an advertisement for life in a gloriously traditional country town. |

But, he acknowledges, life isn’t like that for many young people in Wellington, particularly if they’re young. Youth today aren't as mentally strong as his generation, he says. “They come up against things at a younger age but can’t handle them.” In his era if you got dumped by a girl you thought “tough”, he says. “For the young blokes now, it seems to be the end of the world. Research generally suggests that between 16 and 20 per cent of children and adolescents have significant mental health problems. The experts tend to agree that in Australia rural youth face the greater risk. They’re more likely to commit suicide to have fata accidents and to abuse alcohol, ”and we suspect depression is higher, though the final data isn’t available yet,” says psychiatry professor Dr Beverly Raphael, the director of the centre for mental health in the NSW health department. The situation is much the same for rural youth throughout the country, she says. If they join the ranks of the long-term unemployed, life itself seems to come to a stop. They have nothing to do and nowhere to go and no-one hoping to see them and - in their minds – no-one who cares if they live or die, which may be why the breakup of a relationship prompts some to commit suicide, “That despairing state lasts 20 minutes,” says Myra Murray. But it may not take them that long to get their hands on a .22. “One of the policemen in Dubbo said the wouldn’t be surprised if nine out of 10 utes around here have a rifle in the front seat,” says Tuana Sanders. AUSTRALIA ISNT THE ONLY WESTERN NATION WHERE THE suicide rate for young males has gone up sharply since the sixties, but the trend is particularly noticeable in this country, says Dr Michael Dudley. His research into suicide rates for 15 to 24 –year-old Australian males suggests that the rate doubled in the cities from the sixties to the nineties but increased twelvefold in small country towns.

Out of sight, out of mind This is a regular occurrence in rural area. Though rural communities are under increasing economic and social pressures (see main story) and youth suicide has reached such disturbing levels, per capital spending on mental health services is much lower in rural areas. “Ther is a critical need for mental health services in rural areas,” says academic Peter Dunn, co-author of a study of psychology services in remote and rural Australia. Dunn blames the profession for an element of the problem. “Psychology sees itself as the main player in mental health but it has taken no proactive role to provide a service to country area.” In his view the profession has let down the 30 per cent of Australian who live in rural areas, and put extra strain on other health professionals in hard-pressed communities. “People out there will use euphemisms to refer to me and what I do,” says community mental health nurse Carol Stanborough. A speaker at the sixth annual NSW Rural Mental Health Conference held in Ballina last February, Stanborough talked of the lack of mental health resources in some of the most isolated spots on the planet. From the Flinders and Far North Community Health Services in South Australia, Stanborough and her colleagues serve an area about one and a half times the size of Spain, including Oodnadatta, Woomera and Coober Pedy. | Based at Port Augusta, they visit such towns for about one day a month. ”It leaves people in those communities to cope with whatever comes up in-between, “ says Stanborough. “They consult with us by phone but we’re not actually there if someone becomes a danger themselves or another.” In remote areas people who fall ill are sedated before being taken to a distant hospital in an ambulance – if one is available. In 1991 the then Federal Shuman Rights Commissioner Brian Burdekin said: “If you have a compound fracture in a remote area, a medical team flies out, stabilises your condition and flies you back to appropriate hospital care. But if you become mentally ill and require urgent attention or acute care, you are put in the back of a police paddywagon and driven anywhere between five and 15 hours.” Since those days there has been one big step forward: the use of video-teleconferencing to put isolated communities in direct touch with hospital staff. South Australia has been quickest off the mark. So far 200 people in that State and about 900 in Queensland have been assessed for psychiatric reasons, using the new technology says Dr Peter Yellowlees, professor of psychiatry at the University of Queensland. But there have been few other advances in recent years, he says.

Dying Young “It’s s small country town, everybody knows you or knows of you.” Ten of those who died were close friends, she says. The committed suicide, overdosed or crashed their cars. “A lot of the guys I know who’ve done it won’t count as suicides but as ‘accidental overdoses ‘ or car crashes when they’ve done it on purpose.” More often than not, she says, “they had got right into drugs or alcohol, probably because there was stuff at home they didn’t want to deal with.” Murray, who sells advertising for the Dubbo newspaper the Daily Liberal, has long been aware of the issues around the spectre of youth suicide.. Her mother, Myra, is a clinical nurse consultant for mental health services in the Macquarie area (see main story). For her part Melinda Murray reports that young people who’ve been in trouble are treated as outcasts by the police, particularly if they’re Aborigines. When she was mugged a year ago, “the police showed me photographs of members of the same black family. It wasn’t any of them. But with one of them, the police asked me three times ‘are you sure it wasn’t him? Someone else might have said it was,” says Murray. “once a certain family has got a bad name, they’ll pull up all the relatives, even if the kid himself hasn’t been in trouble.” Something comparable happens to many of the kids who end up seeing mental health workers like her mother. “The teachers have all told them they’re crap and they’ll never get anywhere. How do you expect a kid to act if you talk to them like that?” Her own friends include young men often reminded how little the world things of them. Now some are dead. In the past eight years Melinda Murray has been to a dozen or more funerals. The last was the funeral of an ex-boyfriend. Murray gave the eulogy. “I shouldn't be doing that at 23,” she says. “At 23, I shouldn't be standing up there and talking about someone’s life.”

|