This article appeared in The Weekend Australian 30-31 December 2006

Slippery slopes

of the job treadmill

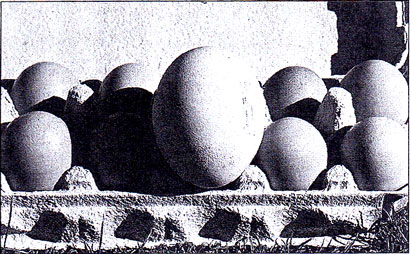

Hold the front page. This week brought the news that people stay in jobs they don't like much because they have bills to pay.With three interest rate hikes in the past year, petrol prices north of $1.10 a litre and credit card debt climbing faster than the mountain of beer cans at the Melbourne cricket ground, keeping the wolf from the old oak portal seems to have been, well, prioritised, by large numbers of people. A survey by the recruiting and human resources firm Talent2 found that "More than a quarter of Australian employees are clinging to jobs they know will not further their careers because they say financial security is more important to them than being satisfied in their jobs". Imagine that. More than a quarter of the 967 people who filled in the online survey were virtually admitting they go to work because they get paid for it. This was a shock to some. The story about it, from Australian Associated Press, said "financial security is keeping a quarter of Australian workers in bed in jobs.." But Talent2 wasn't talking about what many others think of as dead-end jobs. There weren't too many check out persons and self-stackers in it's sample. Talent2 manager Geoff Whytcross says that those surveyed would be earning more than $50,000, which is more than most earn, believe it or not. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, in August 2006, average weekly earnings were $835.60, or $43,451 a year. But the survey points to an interesting phenomenon. Even people on what Whytcross calls " mid-level executive salaries " (still shy of six figures) may feel too insecure to leave jobs that give them neither satisfaction nought hope of advancement. It seems some feel as pressed as the unskilled workers who are the underdogs of the labour markets hierarchy of supply and demand. Earlier this decade I joined them, taking unpaid leave from The Australian and sampling life as a cafeteria attendant, check out chick and cleaner, to research a book about low-wage work. I was offered one job, packing and sorting eggs in a factory on the edge of a country town, five minutes after sitting down for the interview. The application form asked if I had ever been convicted of a criminal offence but said "applicants are advised that answering YES to this question will not automatically exclude them ..." The management would have given anyone a job, that much was clear, but the women on the production line carried on as if jobs were scarce, warning new employees they would be slung out unless they slavishly followed orders. It was as if they had succumbed to the culture of fear infiltrating workplaces. People fear for their jobs as a result of the message drummed in to them for decades. Employers and employer groups, governments and media all have played their part. Pausing only to pick up their short-term incentives, long-term incentives and options (not to mention the success fees they can squeeze from merges), the chief executives who are the real beneficiaries of the boom busy themselves reminding employees, whose jobs have become even more precarious, they have to be more productive or, in the mantra of the present day, more "flexible". | But the flexibility enshrined in the Work Choices legislation is one-sided, to say the least, privileging individual agreements and any form of collective bargaining – though the individual agreements are based on the ludicrous pretence that workers in an egg factory or in a nursing home are on an equal footing with their managers when it comes to negotiating their agreements. Now it turns out that some of those same managers feel uneasy enough about their own future not to leave jobs that have become routine and boring. There is no reason to stay in such jobs, according to Whytcross. Since unemployment is down and job vacancies are up, "this is the time to make that move into your dream job". If you go online, you find the same refrain from other recruiting firms (who make their money when people change jobs, of course). For his part, Talent2's Whytcross Told a journalist for AAP: "Often people moan about their job but they are happier being there than thinking of having to go and find a new job... Perhaps it is the fear of the unknown." Fear of the known may be more of a problem. Mere assurances that unemployment is lower and job vacancies higher than they had been in years won't calm fears nurtured over the decades, especially with all the flexibility on offer for the growing legions of casuals, part-time employees and the sub-contractors forced to cover their own workers comp and superannuation. Some experts believe that the rapid advance of precarious employment is just beginning. At a business seminar at Deakin University in Melbourne several weeks ago, Paul Blyton, the professor of industrial relations at Cardiff Business School in Britain, suggested the debate about flexible working arrangements would soon be overtaken by a debate about access to labour and employment. Blyton, and honorary professor at the Deacon Business School, says human resources and other such corporate functions will gradually become obsolete as companies cease to "own" labour with its inherent risks and overheads. That responsibility will shift to labour-hire companies, who will be like the gang masters of the early industrial age, or to the workers themselves. The changes in the labour market will further polarise employees into winners and losers, he says. Those with the skills that are much in demand will be highly paid, while those lacking the skills will be at the mercy of the economy but without financial compensation for the insecurity. This will not be news to my former colleagues at the egg factory: some have been employed there as casuals for more than 10 years, but the work was steady, at least until the day the owner came to tell them their division was being sold. Elisabeth Wynhausen is the author of Dirt Cheap:Life at the wrong end of the job market, published by Macmillan Australia. |