This article appeared in The Australian 6 September 2008

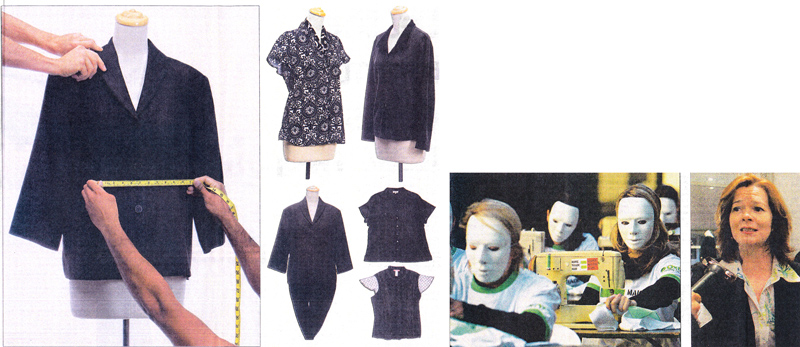

Life's a stitch: Oxfam members protesting against the exploitation of sweatshop workers. Protecting outworkers: Michele O'Neil

Following the Threads

Inspired by calls to wear more ethical fashion, Elisabeth Wynhausen uncovers the global origins of our clothesTHE suit was a beautiful dove-grey. The cropped jacket had a rounded collar and three-quarter sleeves. Once the trousers were taken up, the whole thing would fit like a glove. It cost a fraction less than $600. If it wasn't the most expensive outfit I'd bought, it was close. But I wanted something special to wear to the launch of my book, Dirt Cheap: Life at the Wrong End of the Job Market, in 2005. I started wondering only the other month if the dove-grey Perri Cutten suit I had worn to launch a book about exploited low-paid workers had been made in Australia by an even lower-paid one. By then I'd decided lo find out about recent additions to my wardrobe. Perhaps knowing more about the garments would help defuse the minefield of ethical dilemmas shopping has become. Now the most desultory shopping expedition can involve a debate with oneself about the ecological footprint of a cotton T-shirt, the dyes used in the treatment of leather or the working conditions in garment factories in the Pearl River Delta in China. • The black shirt: The first thing I buy after deciding to deconstruct my wardrobe is a black linen shirt with a stand-up collar, made in China for Simona. Early in the summer I pay $169 for it at the Simona concession in David Jones. By the time I speak with Simona chief executive John Recek later in the season, the shirt is on sale for $119. Simona's linen garments are manufactured in a particular factory in China, from linen also sourced in China, Recek says, emphasising that his company is closely involved in the process. When Recek's mother and stepfather started Simona in 1963, most garments bought in Australia were made in Australia. These days a little less than half of our clothing is imported and about one-third comes from China, according to the most recent figures available. Some Australian companies simply buy the finished garments, for instance, from the trading houses in Hong Kong that are the usual intermediaries between foreign buyers and Chinese factories. Simona deals with four Hong Kong companies that also own factories in China. "We're not buying product off them, we're giving them our designs." Recek says, when I meet him at Simona's offices in the inner Sydney Suburb of Chippendale. I have heard that the agents for factories in China won't accept orders for fewer than 300 garments in the one style, without imposing additional charges, since US order of single styles are in the tens of thousands. But with demand in the US slowing, there is a little more flexibility, according to Recek, who has just visited the Hong Kong companies Simona deals with and says he was impressed by conditions in their factories there. Does he have any idea of the wages of workers in mainland China, for instance in the factory where my linen shirt was made? "I don't ask. They wouldn't tell you anyway," he says. "It's actually not my problem. But what I can tell about the companies I deal with - after being in their offices - is that I would be 100 per cent certain they're all doing the right thing as far as Simona is concerned." It costs his company about $30 to $35 a garment to get the shirt made and landed in Sydney, about half what it would cost to make it locally Recek says, though the local quality is inferior in his opinion "You just get a better product made in China." But Simona still has 70 per cent of each season’s range made in Australia, partly because of the turnaround times and partly because the company produces limited numbers in each style. That means Recek is competing with companies willing to tum a blind eye to the fact some of their contractors are using outworkers who they pay anywhere from $4 lo $12 an hour though typically $6 to $8 an hour, without sick pay, holiday pay or superannuation (and often paying them off the books, which gives them another hold over outworkers too frightened of the authorities to complain). More forthright than some fashion industry executives I interview, Recek oscillates between disbelief that anyone is working for $6 an hour and fury at the unfair advantage it gives unscrupulous employers. "How come we still have such a sweatshop industry still going on in Australia?" he says. "You can walk into Kmart, Target, Coles, Myer, you can see product that people cannot make for the price they're selling it at and it's made in Australia. Forget about working conditions in China for a minute. How do they get that done here? I know what I have to pay. They must be paying $2 a garment." But Recek is also annoyed that outworkers in Australia have the nerve to complain about it. "It's a thousand times more than they were getting in China," he says. "Some of those people could go back to China where they get a bowl of rice once a month and they'd realize how well off they are here " The cotton shirt: Whether their garments are made up the road or in the Pearl River Delta depends on the size of the order, say Kerne Yelland, National Sales Manager for Simone Turpin, a label that first swims into my consciousness when I buy a Simone Turpin cotton shirt. l pay $125 retail. It was $49 wholesale, Yelland tells me, during an interview in the Waterloo, Sydney, showrooms of Gordon Smith Marketing. The company behind Simone Turpin and five other brands. Yelland says she will tell me the story of the shirt from the beginning. Like much fashion in Australia it was inspired by a garment the designer saw overseas "Unfortunately it's the Australian way of design. We always go to the rest of the world first for inspiration because they're a season ahead… That's just the way it's done.'' Rather than buying the garment, the designer photographed it in a shop in New York. "The designer gave it to the pattern maker and said, 'Here's the picture. I'd like you to make that shirt.' What we actually did (was) we added the sleeves " |

The cotton, a blue and white jacquard print, was imported by another Australian company and, as far as Yelland knows, came from China. Machinists employed by the company made the prototype and the samples in the cotton print, then showed them to retailers, along with a skirt in the same fabric and some navy T-shirts. Only a few hundred of the shirts were ordered so they were made in Australia. But where it was made is more difficult to pin down. Yelland thinks the shirt may have been cut and sewn at a factory in the Sydney suburb of Marrickville but isn't sure. "There are several small factories that deal with lots of different labels. We would just be one of their customers " But is the factory subcontracting' some of that work? Could my cool summer shirt have been made by an outworkers bent over her sewing machine in a stifling garage (and, if that's the case, has that factory registered the names of its subcontractors with the NSW Industrial Registry, as required under a state law set up to protect outworkers)? "The girl in production can tell you definitely , but as far as I'm aware this was done by the guy in Marrickville and he has his in-house machinists," Yelland says. "Whether he's got an outs1dt source of workers, I don't know.'' I never get to the factory where my shirt supposedly was made. I hear no more from the people in production Unfortunately, the production manager will be busy all month, Yelland says. The grey skirt: I am at Number One Clothing.ma dreary industrial strip lined with small factories, in Altona. Melbourne. Number One Clothing is one of the suppliers for Ojay and I'm hoping to map the supply chain of my new $99 charcoal-grey Ojay skirt, in a nubbly looking polyester-rayon blend. The factory's roller-door entrance is open. A Vietnamese-language radio station is on full blast. There are 10 or II people at work. Some are pressing clothes using heavy counter weighted irons. The workers on the far side of the factory are unfurling bolts of material on cutting tables. Factory owner Wyn Nguyen asks if talking to me can get him in trouble. I hope not, I say truthfully. In fact he has been in trouble already Number One Clothing was one of a bunch of companies caught out after failing to register with the Australian Industrial Registry, a requirement under the federal clothing trades award for any employer getting work done outside his factory by other contractors or outworkers. "The union prosecuted Number One Clothing in the Federal Court in 2006," says Michele O’Neill state secretary of the Victorian branch of the Textile, Clothing and Footwear Union of Australia When Nguyen goes to answer the telephone, I wander along the racks of finished garments, inspecting the labels. There aren't any nubbly skins, Just pants and jackets. I have lost count of the dozens of Ojay pants suits when I notice the Perri Cutten label on another rack. The union’s O'Neil later tells me Perri Cutten was also prosecuted in 2006 for failing to keep sufficient records of dealings with the outworkers in their supply chain. "'They have since met the minimum legal requirement of being registered to give work out" O'Neil says. The company doesn't return my calls but documents Perri Cutten has lodged with the Australian Industrial Registry list: "No One Clothing" - the name on the board outside the Altona factory as one of its contractors. Such documents can help expose the sometimes intricate layers of a supply chain, allowing the union to locate outworkers to find out what they're paid. Rather than discussing his dealings with outworkers, Nguyen rejoins me in his factory and says he has been in the clothing industry for 20 years but things are getting worse. "Not like before, now It's harder." When production managers from the fashion house. are negotiating prices they remind him how little it costs to get a suit made in China. "If they say, 'I can get suit made for $10’ they can. Over there, labour cheap," he says. How does he compete? "We only know that Number One Clothing gives out a lot of work, both to outworkers and to other factories," O'Neil says. "Now we find that the company is yet again in breach of the same provisions: they're not registered. And Ojay appears to be refusing to take responsibility for the actions of people in its supply chain." It isn't just Nguyen gloomily predicting the clothing industry in Australia will not last much longer. His biggest customer seems to share this view. According to Fairwear campaign co-ordinator Liz Thompson, Ojay owner Henry Lee told Fairwear in 2004, 2005 and 2006 and again in 2007 that his company was moving production offshore. Asked if he wishes to respond, Lee instead emails me two newspaper columns arguing that campaigns by the unions and by churches aimed at ensuring outworkers get their due are destroying the clothing industry in Australia. The black jacket: Elsewhere in Melbourne's west, in a half-derelict row of shopfronts along Commercial Street, Maidstone, I check out addresses of contractors I photocopied from documents lodged at the Australian Industrial Registry. The company trading as Anthea Crawford lists Vi View, at 5 Commercial St, as one of its contractors. I'm there hoping against hope to find out something about my latest acquisition, a new jacket I've just bought in the Myer store. I'd been browsing through the racks in the name of research when my normal common sense deserted me; I tried on a double-breasted black Anthea Crawford jacket with gold-rimmed black buttons and forgot I'd resolved never again to buy a garment without looking into its antecedents. It set me back $489. So much for the constraints of ethical consumption. The label on my new wool crepe jacket says "proudly made in Australia". The jacket is first class. But I'd like to know about the production process. |

One of two shareholders in Anthea Crawford is Voyager Distributing Company, one of Solomon Lew's web of companies. Six years ago the Textile. Clothing and Footwear Union of Australia prosecuted Voyager after Anthea Crawford failed to lodge the required Australian Industrial Registry documents showing it was giving out work. Voyager also produces some of the Myer house brands. When the union prosecuted the company last year for similar breaches by other brands, Voyager insisted that the agreements it came to with the union were also being made on behalf of Anthea Crawford, O'Neil says. With this in mind I ask Anthea Crawford national Merchandising manager Warren Turner about the identity of the machinist who laboured over my jacket. He passes on an email from the production manager saying that the Vietnamese man who oversaw the production of that particular style is "a registered subcontractor who complies with the code or practice of this business. He has quite a few machinists who do the assembling part of it and other staff to do the cutting, the finishing and the pressing of the garments". The email doesn't say where, exactly, these machinists assembled my jacket. Instead Turner says the company is in constant contact with its suppliers "Anthea would know each one personally, they're forever coming into the office''. The T-shirt: But I've gone on to look into the origins of another summer purchase, a fitted swallow-neck T-shirt made in China for Stitches, a more moderately priced label. It retails for $89. The T-shirt is in a fresh navy and white print inspired by the design of a 1950s skirt the company's head of design, Gavin Boardman, says he picked up in an op shop in Parts. When his staff completed the artwork for the design, Stitches sent 11 to a mill in South Korea that printed the pattern on a poly-spandex fabric. "We don't buy 10,000m of a print, we might buy a 1000 to 2000m. Because we don't order massive amounts of it, we pay some sort of surcharge," Boardman says when I meet him, general manager Anthea Hampson and production manager Marc Charalambous the Stitches office in inner Melbourne. When the sample was made, fitted, remade in the right fabric and refitted, the garment was "specced" and the details emailed to the factory in China. "We deal directly with the factories, we don't have agents." says Charalambous, explaining that my poly-spandex top was made at a factory in China set up specifically for Stitches. "It's got 100 staff, which is little for China, and perfect for us. He probably makes for us around 100.000 units a year." Charalambous, who has often been to the factory, is convinced the workers are doing all right. "The salaries have gone up. They're getting approximately $US240 ($294) a month," he says. Anita Chan, an expert on labour conditions in China, who is a visiting research fellow in the Contemporary China Centre at the Australian National University, says $US240 a month is now the equivalent of about 1645 yuan a month, “which is the high side but not impossible". But it would mean they're earning more than many other garment workers in factories in China. In 2006 Chan and Kaxton Siu. a colleague now at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, interviewed garment workers from four factories in Shenzhen City that supplied Wal-Mart m the US. Despite widespread reports of labour shortages in China, they found that in driving down the prices of goods. Wal-Mart is driving down migrant wages in the export sector. The same thing is happening in the remotest pockets of the globe as big retailers exert downward pressure on the wages of migrant workers. There could hardly be a better example than Saipan, in the western Pacific, one of the 14 islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, a far flung territory of the US where US labour laws do not apply. A reference to a court case there prompts me to dive into my cupboard to check the labels on the black Anne Klein blouse, Jones New York high-necked T-shirt and grey Ralph Lauren pants suit I bought in Macy's in 2006. All say "made in the Northern Marianas islands USA". I have unknowingly bought clothing made in a place that has become a by word for sweated labour. The Saipan garment factories opened in '80s to circumvent the quota system that set limits on the amount of clothing entering the US from any other country. That rule didn't apply to Saipan and soon recruiters were bringing in temporary migrant workers from Asia, charging them thousands of dollars in recruiting fees for the privilege of earning a wage that last year reached $US3.55 an hour. In Nobodies; Modem American Slave Labor and the Dark Side of the New Global Economy, author John Bowe reports on the 1999 class action suit 30,000 present and former migrant workers from Saipan filed against 25 American retailers, among !Item Polo Ralph Lauren and the Jones Apparel Group (which includes the Anne Klein brand), the Gap, Target, Liz Claiborne and Calvin Klein. The case was eventually settled for $US20 million in unpaid back wages and overtime. Since then. the quota system has been changed, the garment factories on Saipan are closing and big retailers are combing the world for other sources of cheap labour. I emailed the customer relations department for Polo Ralph Lauren to ask if they could help me map the supply chain of my pants suit. They wrote back: "Polo Ralph Lauren requires all licensees, vendors, contractors and subcontractors to adhere to strict operating guidelines, which cover the following: health and safety, wages and benefits, working hours and overtime. freedom of association, child labour, customs compliance, environmental regulations, as well as forced labour, prison labour and discrimination." They didn’t mention Saipan, though. Photo Captions: |